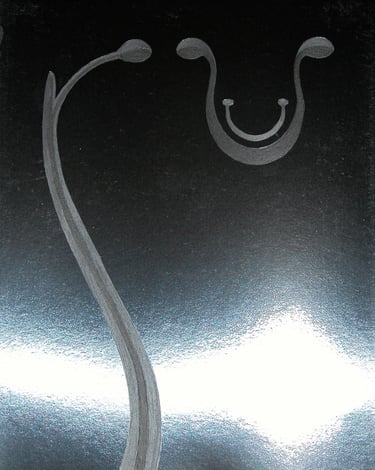

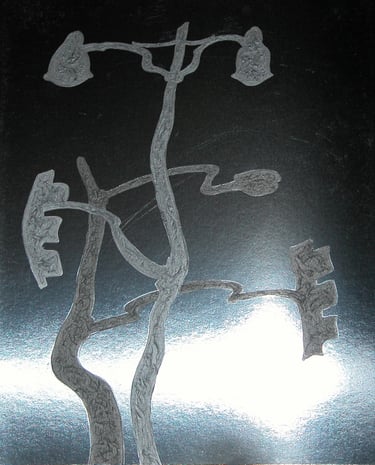

Luminaries

Study on the phenomena and noumena of light.

Whether a wave or a particle, a venerated mystical paradigm or a measurable substance open to scientific investigation, the interpretations of the nature of light abound in every age and culture.

Fact or fiction, a story is always true to those who recount it and those who can relate to it. Mere myth may not be so opposed to proven fact for as cultural narratives, they are both more revealing of the storyteller than the reported subject, in and of itself.

Thus, every period and tradition fashions its own story of light and striving to manifest its own vision, discloses its particular relationship to the faculty of sight.

Here then is a short list of the early luminaries of the western world:

For the ancient Egyptians light emanates from the eyes of their deity. All that is seen is encompassed by the gaze of their sun god Ra. His eye reigns as their most potent symbol and it is said that humankind sprang from its tears.

In Plato's exegesis of the sense of sight, the eye is a lantern causing a gentle light to issue from it, an interior spark that melds with daylight, thereby forming a single , homogeneous body of light. Plato uses sight as a metaphor for all knowing

Zoroastrianism (2000 B.C.), and especially Manichaenism (200 A.D.), are religions of light that establish a strict duality between light which is upheld as the universal good and darkness, the evil realm of base matter.

While maintaining that the eye emits beams of light, Euclid (300 B.C.), proposes that these rays of sight are carried in straight lines, at spaced intervals from one another. The visual ray is no longer a luminous and ethereal emanation but a geometric model susceptible to deductive logic and mathematical proof

Lucretius (90B.C.), proclaims that objects emit thin films of matter that are continuously flying off their surface. These ethereal particles impress themselves upon our sense organs to produce our perception of them. An object held in the dark, he purports, is recognized as the same object seen in broad daylight due to the films it transmits, making his theory of sight more akin to the sense of touch.

Alhazen (11th century), conducts extensive experiments on the propagation of light and its dispersion into color. He refutes the theory that the eye is the dispenser of light and through his studies of the rainbow, shadows and eclipses, maintains that rays originate in the physical object of vision and not the eye.

Grosseteste (13th century), a clergyman and one of the first medieval scientists, straddles both a religious and empirical understanding of light. God creates lux, "light at its source" and man, through hypotheses and experiments on the properties of lumen, "reflected light", seeks to reconcile its complex variables into the primal cause of its creation.

Brunelleschi (15th century), picks up two panels with the aim of depicting architectural views of Florence and makes the first drawing in linear perspective. In his mathematically proportioned system, rays from the eye extend to every point of the seen object, forming a cone with its apex at the pupil.

Newton (1642-1767), suggests that light has a particle nature and by defining its "least parts", goes on to explain optical phenomena in terms of corpuscles. These particles travel in straight lines at great speed, reflect from mirrors in predictable ways then entering the eye, change direction by speeding up to the retina in a phenomenon called refraction.

Meanwhile, Huygens (1629-1695), proposes the existence of a medium between the eye and the perceived object, a rare substance that fills space called ether. A luminous body causes some change in the constituency of this intervening medium which in turn, affects the eye. This early inkling of the wave characteristic of light remains supplanted by the dominant particle hypothesis.

Thomas Young (1773-1829), directs a beam of light through two pinholes to project a pattern of alternating bright and dark bands on a screen. The resulting phenomenon known as diffraction, displays the interference pattern typical of waves. His experiments firmly demonstrate that light bends around the edges of solid objects, corroborating the wave theory of light.

Maxwell (1831-1879), advances the view that energy radiated in the form of a wave is the result of an electric field interacting with a magnetic field. While caused by the acceleration of a charged particle, the variation of intensity within this field makes visible light one among many types of electromagnetic radiation.

Planck (1858-1947), while studying the radiation of blackbodies (substances that absorb all and reflect none of the energy that falls on them), determines that the resulting radiation is not emitted continuously but in minute units or quanta of energy. Ushering quantum physics, he maintains that light exists in a dual mode. In some cases it behaves like a wave and in other instances it displays its corpuscular nature as a photon.

Einstein (1879-1955), extends the photon hypothesis with his elucidation of the photoelectric effect. When the discrete particles of light strike a surface they release an additional kinetic energy in the form of electrons. His theory of relativity dispenses with the ether and predicts that the maximum velocity of a material particle is the speed of light in a vacuum.

Much has developed since then and the continuing research in the field of optics have assuredly led to rapid technological developments. While the revolutionary advances of quantum physics disclose attributes of light fraught with ambiguities, a growing dissatisfaction with the supremacy of vision, revered since antiquity as the noblest of senses, urges a deconstruction of the scopic regime that informs our notions of observation and speculation. Yet another consideration, one that comes as no surprise but like an itch, begs to be posited, is that the above list of scientists amounts to an exclusive lineage of men. These luminaries line a one-sided history that privileges presence over what it construes as absence, visible proof over the invisible matrix that subtends the very possibility of seeing. A slow erosion of visually defined notions of truth imparts that a black hole may constitute not so much the absence of light as an energy field with a velocity that exceeds the speed of light.

To weave another tale, we may recall Marcel Duchamp's enigmatic "large glass", the two panels of which set up an unbridgeable separation between the sexes. Our men of science are lodged in the machinic arrangement of the bachelors while their object of study, the elusive substance they are in pursuit of, is a bride that will never marry. She, the most immeasurable of elements, holds her quantum qualities suspended within herself. In their difficult courtship, each and every path followed by these candidates winds up to a gate that shuts close upon their approach and yet, opens wide as they turn away. Because their eyes fail to apprehend her formless splendor, their scrutinizing gazes fall like blind gravel in the plenitude of her self-touching waters. Better the howl of coyotes in the dead of night, the unfolding of a plant in the heat of the sun and the dancing of plankton in a sea that dissolves the outline of forms and their mirrored images.

Explore the artworks

of Ely Tahan on social media:

CONTACT

© 2025. All rights reserved.